I believe for example that one of these days and maybe tomorrow, Birmingham, Alabama will probably blow up, and if Birmingham blows up, it will not just stretch to Atlanta, it will stretch to Boston.

There's a kind of fuse, there's a kind of, undercurrent, there's something which unites all the Negros in this country, so that what happens in Birmingham can blow up Harlem. It has happened before, and unless we are extremely swift and miraculously swift, it will happen again.

— James Baldwin [quote from Malcolm X Debate “Black Muslims vs the Sit-ins”, 1961]

Did you know that in the 1950’s, the black community banded together to infiltrate the KKK, and formed a 50-member militia to stop their homes from being bombed? Today, we’ll learn about about Dynamite Hill, the nickname of a neighborhood in Birmingham, Alabama that was bombed at least fifty times in eighteen years.

Most of us probably already know about Birmingham as the site of Martin Luther King’s human rights campaign, which ultimately resulted in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But I wanna get hyperlocal and talk about the experiences of residents of a specific neighborhood in Birmingham — aptly nicknamed ‘Bombingham’ in the media at the time. These experiences sparked a fuse of radical resistance that James Baldwin has so forebodingly said: “unites all the Negros in this country”.

Lighting the Fuse: The Explosive Background of Dynamite Hill

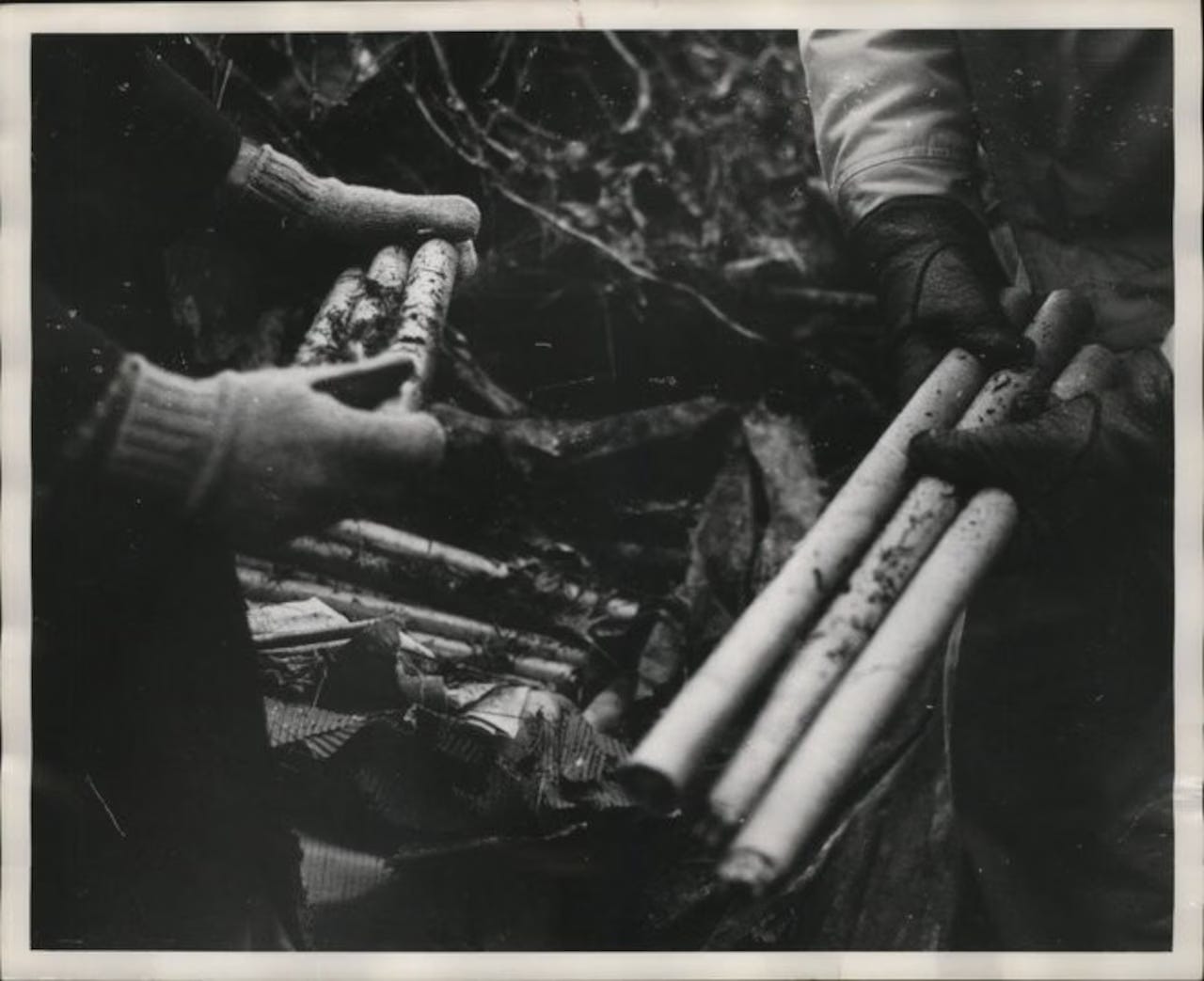

In 1947, Arthur Shores filed the first legal challenge to Birmingham's segregated zoning laws on behalf of Samuel Mathews. At the time, the city had segregationist zoning policies and Shores launched a successful yet arduous legal battle, fraught with systemic barriers, which ultimately forced the city to issue a certificate of occupancy to Mathews. The night after the Federal government issued Mathews his certificate, his home was bombed with sticks of dynamite. But that wasn’t the end of it; in a 1985 interview for Eyes on the Prize: America's Civil Rights Years, Shores describes the constant terrorism that the North Smithfield (Dynamite Hill) residents faced:

We went into the federal court and the court directed the city to issue the certificate of occupancy. And the night after this certificate of occupancy was issued, that house was completely destroyed by dynamite. Then of course, we next had to file a suit to have the ordinance declared unconstitutional, which was finally declared unconstitutional by a federal judge. And that house was dynamited and one end was blown off. And then, of course, right across the street, Center Street, on the side of Center Street where I lived, half of that block was zoned for white and the other half for black. Well, blacks began to buy property on that half, and whites across the street begin moving out. They sold their houses to blacks, and before black could move in that house was, was blown up, dynamite, or either, or either burned.

With every newly purchased home at high risk of being bombed, and no substantial support from the local police in investigating the culprits, Dynamite Hill residents developed a plan to put a stop to the steady barrage of domestic terrorism they were facing every few months. Shores continues:

And what broke it up there was, the blacks had hired a white member who infiltrated the Klan, and the Klan notified him that on a certain night, a certain house that had been recently purchased, would be either burned or dynamited. And at the appointed hour, blacks had secreted themselves across from this house, and when the whites came up, they opened gunfire. One white was killed and several were wounded. Nothing was ever placed in the paper about it. And that broke it up. There was no more burning there until several years later in 1963, I believe it was, when the schools were integrated.

In retaliation to what can be reasonably deemed an act of war on the black community of Smithfield by white supremacists, the black community not only organized themselves into a community defense unit, but also enlisted the espionage of local white folk to gather intelligence on future bombings. Because they were prepared for the attack, black Smithfield residents were able to neutralize the terroristic goal of the white supremacists targeting them, potentially saving lives.

Unfortunately, as Shores explains, there are no known local publications that can directly corroborate his story. In examining similar events in history, a liberally informed opinion might suggest that if the local Birmingham World newspaper were to talk about the shootout, it may have led to more violence, rioting, or even an all-out air raid of the black locals (as evidenced in the Tulsa race riots). A radical opinion might suggest that Bull Connor — the local, proudly white supremacist police commissioner — didn’t want to broadcast to other black folks in the south that they could organize and successfully disrupt white supremacy… one can only speculate. That said, what I could find was a source that describes the Smithfield community as enlisting the help of a private detective to find out who the culprits of the bombings were:

Black leaders therefore quickly came to the conclusion that they would have to circumvent the police to end the terror. In their first effort to do so, in the summer of 1949, they hired a white private detective, Herbert Browne, to try to find out the identity of the bombers. But police, learning of this initiative in mid-August, promptly put a stop to it by arresting Browne for doing business without a license (Dividing Lines, page 163).

I think it’s important to note here that police remained apathetic as the black community suffered an onslaught of racially motivated terrorism and bombings, but immediately took action to arrest white folks who took it upon themselves to investigate the acts of terror in their neighboring communities.

Herbert Browne may have been the KKK infiltrator mentioned by Shores, but I can not definitively say that they are the same person, nor find additional information about Browne without accessing the Birmingham World archive. Nonetheless, these accounts — as described secondarily by Arthur Shores and by J. Mills Thurton III in his book Dividing Lines — are incredibly valuable, offering insight into white co-conspiratorship in countering white supremacist violence during the Civil Rights Era.

Defusing the Bombs: Organizing the North Smithfield Civil Defense Unit

After the arrest of Herbert Browne (and/or ostensible loss of a klan spy), and continued inaction from the Birmingham Police department, black Dynamite Hill residents attempted to find allyship from the state government and highway patrol. Thurton continues in Dividing Lines:

Thereafter blacks turned to the racially moderate Governor James Folsom and the state highway patrol. At the end of August the highway patrol began providing protection in North Smithfield, and as we have seen, the bombing then stopped until the following April. When the violence resumed, Governor Folsom met in May 1950 with a black Smithfield delegation consisting of the Protective Association’s Coar and Hollins, attorney Arthur Shores, World editor Emory Jackson, and civil rights activist the Reverend James L. Ware. Following this meeting, Folsom offered a reward for information leading to the apprehension of the bombers and ordered his three state investigators to enter the case. And on June 25, Folsom traveled to Birmingham to denounce racial prejudice in an address to more than a thousand blacks at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. But without the cooperation of the Birmingham police, the state investigators were unable to make any progress, and the posting of permanent highway patrol guards in the area was impossible given the many demands on the force (page 164).

Uncooperative, unhelpful, and apathetic police have always been a part of the (black) American story. It is a testament to our survival ability that we have found alternative ways to secure our own safety without the help of the state, instead ensuring safety through collective action, strategic organizing, and transformative/restorative justice. What demarcates the Dynamite Hill story so groundbreaking in an overall history of oppressive resistance and survival is how the local black residents of Smithfield retaliated to police and state inaction by self-organizing a “civil defense” unit, a federally recognized paramilitary organization. Thurton continues:

However, the cold war, intensified just at this time by the outbreak of fighting in Korea, adventitiously supplied Smithfield’s blacks with a more permanent solution. They applied to federal authorities to organize a civil defense unit for their neighborhood. They thus gained helmets, armbands, and badges—and, most importantly, official sanction and justification for maintaining a paramilitary organization. Beginning apparently in early 1951, following the bombing of Mrs. Monk’s home, for the next fifteen or more years the fifty-member Smithfield District Civil Defense Reserve Police patrolled every night, initially under the command of letter carrier Robert F. Walker and later of postal maintenance worker James E. Lay. At first their efforts were focused on Smithfield itself, but as Klan violence spread to other areas after 1956 the civil defense unit extended its coverage as well. By 1963 it was assisting in providing security for five black sections of the city (Divided Lines, page 164).

Taking advantage of the conflict in Korea (and the USA’s bloodlusted capitalization on international anti-communism), black residents of Dynamite Hill organized themselves into a federally authorized paramilitary organization in 1951. The “civil defense” unit, officially recognized as a tax-exempted, 501(c)3 organization by the IRS, performed patrol duties every night for fifteen years and, by 1963, had expanded to four additional black districts (Yohuru Williams and Jama Lazerow, Liberated Territory). The creation of the Smithfield District Civil Defense unit was effective in protecting black residents, so much so that led to a four-year pause* in bombings from 1958 until 1962 (250, Dividing Lines).

* - note that bombings did not stop for everyone, as there were isolated acts of racially-motivated violence against black Birmingham residents outside of Dynamite Hill. Four churches were bombed in 1962, and at least 10 assaults and shootings of black Birmingham residents occurred, according to Christopher Hewitt’s Political Violence and Terrorism in Modern America (view citations below for more information).

Putting Out the Fires: The Tactics and Triumphs of the Civil Defense Unit

The Smithfield Civil Defense unit emboldened an already strong mutual aid infrastructure in the neighborhood. Bombed homes were rebuilt by black community members such as Leroy Gaillard, who owned a local construction company. He also used his network to furnish vehicles and police scanners. Gaillard describes the operations of the neighborhood patrol in a 1998 Interview with the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (retrieved from National Park Service Registry of Historic Places document):

"We organized what we called a North Smithfield Protective Association. It comprised . . . most of Smithfield from 8th Avenue to 13th or 14th Avenue North .... We patrolled that area and I had radio equipment, cars, and trucks that I loaned to the association at night when we weren't working. They patrolled the neighborhood. Some of my trucks were big trucks, like a dump truck that had a radio in it. So they put it in a stationary position, they just parked and observed. Small trucks and cars they would just patrol the neighborhood all night. I would meet them every night at 6:30 and we would dispatch the cars and trucks out. I had a radio monitor in my bedroom so I could monitor my cars and also monitor the police band and the police department." (Section 8, Page 15)

The North Smithfield Protective Association was a fully-functional community defense unit, complete with helmets, badges, and radios to communicate with each other and monitor the local, adversarial police department. In a 2015 interview with Garret Mathews, Gaillard reflected on the unit’s independence from the police, remarking: “we did it all ourselves. Calling the cops would have been a waste of time. They wouldn’t have done anything.”

Smithfield’s civil defense unit was dedicated to protecting not just black residents from white supremacist violence, but any civilian caught in the explosive, interracial violence of Bombingham. During the Birmingham Riot of 1963 — which was sparked by several bombings, including the home of Alfred Daniel King, Martin Luther King’s brother — the black Smithfield civil defense unit rushed into chaos. Thurton writes about the uprising in Dividing Lines:

There had been a time when blacks might have responded to such Klan outrages with fear, but the demonstrations had greatly strengthened their resolve not to allow themselves to be intimidated. It was a Saturday night, and the nightclubs and bars surrounding the Gaston Motel were filled with blacks who, at the sound of the blast, poured into the streets. There then ensued a riot that lasted for much of the night. Sixty-nine people were hurt, and property losses amounted to more than $100,000. The toll could well have been even greater had it not been for the efforts of the black Smithfield civil defense unit. Under its captain, postal worker James E. Lay, twenty of its members labored heroically until dawn to contain the violence. One of them, Sylvester Norris, succeeding in driving a city fire truck through the mob to a blazing building after a barrage of stones from rioters had kept whitefiremen from doing so. Lay personally saved the life of a white cabdriver whom members of the mob had knifed. (Dividing Lines, page 331)

Under the leadership of Captain (and part time postal worker) James E. Lay, the Smithfield Civil Defense unit spent the entire night both de-escalating black rioters and saving white civilians caught up in the violence. Their bravery — however — did not exist without consequence:

The heroism of the Smithfield civil defense unit unfortunately brought it to the attention of the regional civil defense director in Thomasville, Georgia, who promptly ordered the unit to cease using civil defense insignia and equipment in connection with the quasi-police activities that had done so much to protect black Birmingham from the Klan’s malice during the past decade. Apparently thanks to the efforts of white moderates and liberals, however, the prohibition was rescinded after three months. (Dividing Lines, page 657)

Once again, I must highlight and contrast the deliberately weaponized inaction of the police and the state here. While conspicuously absent during the violence and rioting, police were swift to act afterward, punishing those brave enough to help, protect, and serve others.

The Perpetual Flame of Revolution: A Brief History of Black Self-Defense

Since being brought to turtle island in chains, black people have a long history of resistance and self-defense, including armed and organized resistance:

In August 1831, a literate Nat Turner led a slave rebellion in Southampton Country, Virginia using strategic organizing, limited resources, and no guns.

In October 1859, one slave and four free blacks (along with white abolitionist and co-conspirator John Brown and his three sons) participated in an armed raid of the federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

In July 1919, Dr. C.P. Davis organized a two-dozen member community guard to protect S.L. Jones — a local black journalist — from being lynched in Longview, Texas.

These are three of many more examples of the black community’s organized resistance that showcase our creativity, tenacity, and dedication to defending ourselves from white supremacist violence. The Black Panther Party, perhaps known as the most famous example of black, communal self-defense, is one organization in a larger network — and history — of organized black survival.

The Fire Is Still Burning: Lessons from “Bombingham”

“Bombingham” was an active war zone for Black residents in Alabama. The violence of American white supremacy didn’t just destroy property—it tore apart Black families and children, shattering lives with explosive brutality. This racial terror existed before the Civil Rights era, persisted throughout it, and continues to be resisted by the black community today. Reflecting on the 16th Street Church bombing where four little girls tragically lost their lives, Leroy Gaillard is quoted to have remembered seeing flesh on the walls. He “knew then that if change was going to come, we would have to help bring it on” (Coming Together: Oral histories from the Civil Rights Era, Garrett Matthews).

During an onslaught of relentless white supremacist violence, Black North Smithfield residents made the radical decision to depend on each other for survival when no one else would help. They had to use creative, clever thinking to gather the resources they needed, and banded together tightly to organize their own collective safety. In an active genocide, those targeted must understand that neither the state, nor it’s auxiliary carceral institutions will ever protect or serve them. The only ones who can lift us out of our circumstances is ourselves. The only ones who can break our chains are ourselves.

As we accept the reality of this new administration — rife with censorship, book banning, miseducation, genocide, denial, imperialism, white supremacy, plutocracy, capitalism, xenophobia, transphobia, misogyny, ableism (and, unfortunately, so, so much more) — let’s also accept the reality of our elders and ancestors who resisted the same kinds of violence. We can learn from their successes, their failures, and their stories, just as they listened to their elders and ancestors to forge new paths to liberation. The legacy of black community defense in groups like the Smithfield Civil Defense unit reminds us that our collective power lies in our effective ability to organize, resist, and care for one another.

If we divest our attention from the oppressive institutions around us, instead investing our attention into our own community, we will find that we will feel safe and protected amongst each other. Police, historically, do not protect us. Our state, historically, actively ignores our cries for help or actively pushes legislation that harms us.

Who can you call when there’s an emergency? Who will actually pick up the phone? Who can you trust to de-escalate a tense situation? Who will help you when the state won’t? It’s time that we answer these questions, intimately and analytically. The brave residents of Dynamite Hill did, and then started organizing. It’s time for our contemporary community to do the same; start organizing a community defense and safety network with your loved and trusted comrades! Start building neighborhood PODDs! Start depending on each other for survival; the reality is that we always have had to, and always will. We are all we’ve got, and it’s always been this way.

I’ll conclude with a really great tweet by @comradesanchez that reminds us not to give up hope and to continue our legacy of self-defense and resistance:

did the enslaved give up? the suffragettes? the mine workers in West Virginia getting shot at? did Gaza give up after over 400 days of genocidal warfare? some of y'all are tweeting with fancy gadgets, full bellies, and roofs over your head. how dare you contemplate giving up!

CITATIONS:

Malcolm X Digital Collection: Black Muslims vs. The Sit Ins, 94.1 KFPA Radio Malcolm X. Website. Accessed February 2, 2025: https://kpfa.org/area941/episode/black-muslims-vs-the-sit-ins/.

Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma, J. Mills Thorton, University of Alabama Press, 2002. Book. Pages 163-164, 250, 331, 657.

Interview with Arthur Shores, conducted by Blackside, Inc. on November 1, 1985, for Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years (1954-1965). Washington University Libraries, Film and Media Archive, Henry Hampton Collection. Document. Page 4. http://repository.wustl.edu/downloads/5q47rq535.

Coming Together: Oral histories from the civil rights era, Garrett Mathews, Plugger Publishing, Website, Accessed February 2, 2025: https://pluggerpublishing.com/civil-rights/interview-19.

Liberated Territory: Untold Local Perspectives on the Black Panther Party, Yohuru Williams and Jama Lazerow, Duke University Press, Durham and London. 2008. Book. Page 164.

Political Violence and Terrorism in Modern America. Hewitt, Christopher. 2005. Westport, Conn: Praeger Security International. Book. (honestly i just ctrl+f’d “Birmingham”, cross referenced the dates and counted lol; too lazy to go back and find the page numbers. seriously. just ctrl+f it.)

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM, United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, August 20, 2007. Document. Section 8, Page 15, https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/daeb70a2-80e2-472f-a758-72b008af4ba7.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

Historicizing Black Resistance in the U.S.

Love this